Hi there, before we get started, here’s a quick note from The Wellbeing Project. Today’s episode of At The Heart Of It features some conversations about mental illness and violence. Listener discretion is advised. Let’s get into the episode.

Welcome to At The Heart Of It, a podcast where we explore issues at the heart of our world’s biggest challenges and their solutions. We’re on a journey inward going into ourselves, reflecting on who we are, listening to humanity’s collective story. Our guides are the visionary leaders, activists, scholars, and practitioners who are changing the world and whose own inner journeys of wellbeing inspire their welldoing.

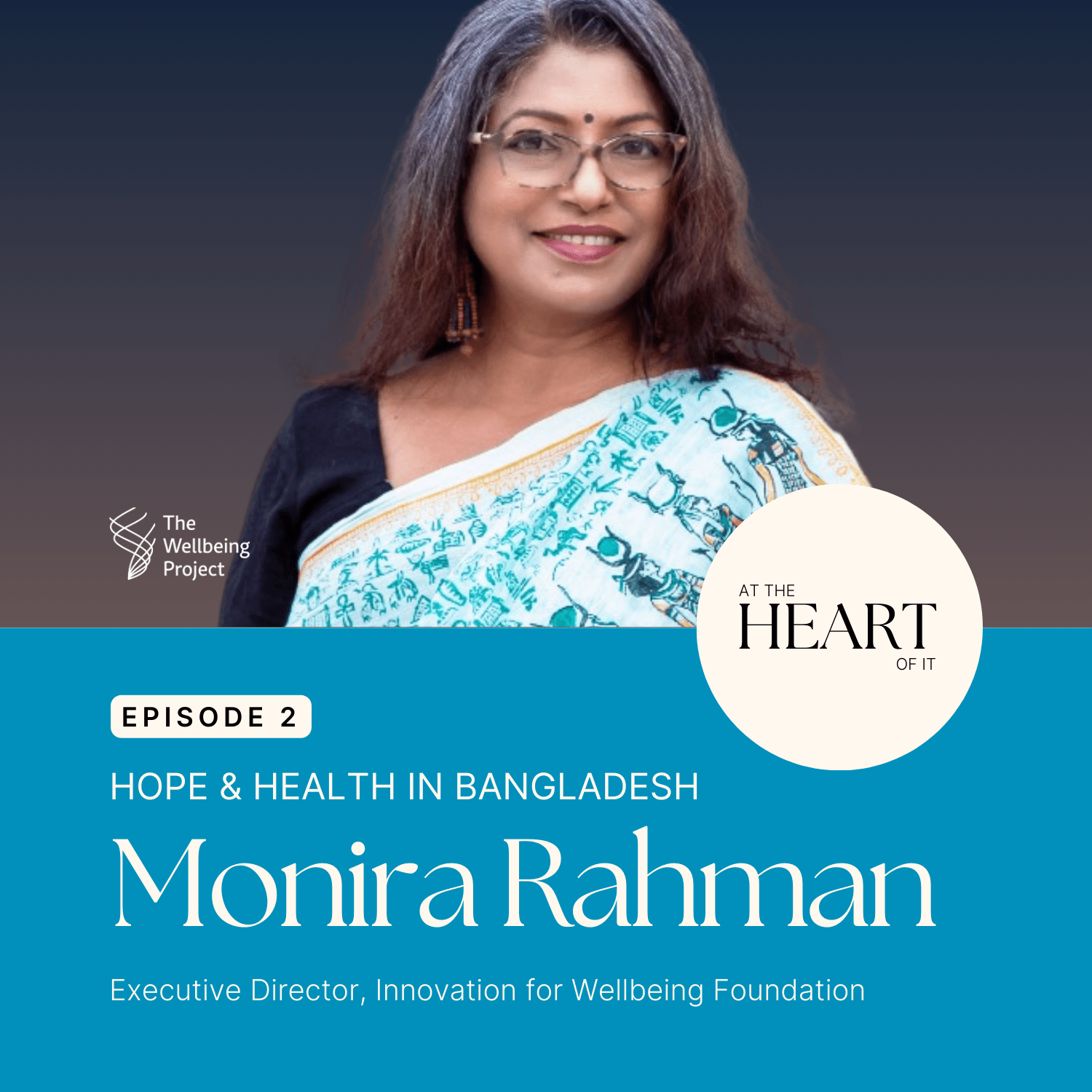

Today’s guest is someone who has dedicated her life to making Bangladesh a safer, healthier, and more inclusive place for everyone. Monira Rahman is an award-winning Bangladeshi human rights activist and Ashoka fellow. For more than 30 years, she has led efforts to transform social behaviours and reform government policies around violence against women and mental health in Bangladesh.

In a conversation live from the lush green gardens of Bangla academy in Dhaka, where Monira hosted the first regional wellbeing summit in Asia, Monira reflected on her life’s work and how wellbeing has inspired welldoing in her career. Throughout her career, she has been an advocate for caring for oneself and for others and today she’s sharing her story and inviting us all on a journey of wellbeing. Let’s get to the heart of it.

Madelaine VanDerHeyden (MV): Hi, Monira. Welcome to the podcast. Thank you so much for joining us.

Monira Rahman (MR): Hi, Madelaine. I’m very happy to join with you.

MV: So, Monira, we are here in Dhaka, Bangladesh. You are an internationally known, award- winning social changemaker. So tell us a little bit about your work and what you’ve been doing in Bangladesh.

MR: Well from my childhood, actually, I knew that there are inequality, injustice, and especially for girls and women in this country who are suppressed, oppressed, and their rights are not acknowledged. They’re not respected. And in that way, I started to find out what can be done or what is the solution.

First, it began with myself, to liberate myself from these limitations. But it’s quite unusual for a Bengali girl, a young girl, an adolescent girl of 13, 14, to be going out and doing things on her own. So it was not that welcomed by my family as such, but my mother was always encouraging me to be educated and to be independent. She was always inspiring me to work for the community, work for the people, serve for the people. So I was involved in many different kind of activities activism for women rights, especially for education for all.

When I was studying in Dhaka University, I was elected vice president of one of the female hall and that was quite rebellious, I should say, because there was military rule and therefore the students’ movement was suppressed even by the law enforcement agencies. So it was a very difficult time, but we really worked together and we got the democracy back. I did my Master’s in philosophy from Dhaka University and my first job was with Concerned Worldwide as a social worker. I was 24 and in a village where the government has a institution called Vagrant’s Home.

That means, for homeless people living on the street, the police sometimes put them in this institution in the name of rehabilitation. So it was a center accommodating 700 women and girls. And my first day was very, very striking. I saw a girl who had her hands tied behind her back lying on the feeder street looking at the sun on a very hot, humid day. And I just untied her and then it was big issue for the institution authority.

MV: And why was she tied up?

MR: Because it was a way of punishing someone. So I was called by the authority, but I answered them that I think any human being would untie her. Why not? So they couldn’t throw me out from the center. Then I found a Jominder building. That means it’s a very old building. It’s an abandoned building. It’s very damaged, no light. And there were hundreds of women there. And the authority said they are all mad, mad people. And Concern Wordlwide told me that I have to work with them. So it was 1992. There were no mental health support services in the country. I didn’t have any mental health background. I didn’t know what to do or how to support them. So I was looking for any model, any organization doing anything about mental health in the country.

For the first time, I came to know about psychosis, neurosis, depression, anxiety. So then I found one organization working with children with intellectual disability. By observing their work, I found some thing quite interesting. I bought some postcards, papers, color pencils, and then I was just sitting in that Jominder building and just seeing how the women respond.

After seven days, some of them came nearer to me.

MV: You were just sitting there and no one was approaching you? No one was talking to you?

MR: No.

MV: They didn’t want to come?

MR: Yeah. And then I found some people were started to fix a particular type of postcard. And I found that maybe that has a connection with them. So I started working on those areas with them. And I really would like to talk about one story that struck me and actually changed my perception about mental health.

So this woman called Rokea. She was a teacher of a village from Kishoreganj. Her husband was also a teacher. In 1974, in our country, there was a huge famine. So the relief was coming through the school and the head teacher was stealing the relief goods. Rokea saw that, and Rokea was raising her voice against the headteacher. Headteacher was not happy, and the headteacher said, “Rokea has become mad. Rokea is mad.” Rokea was trying to prove that she is not mad. Rather, this man is actually corrupted. But no one knew her, and a village woman was not supposed to raise her voice like that in public.

So she was held and tied and she was taken to a psychiatric department. And when she was going there, she thought she will complain to the education minister about the teacher. But when she was under treatment, under medication, she lost her consciousness. And, at one stage, she actually went out of the hospital. No one knew about that. She was on the street for several years. She can’t say how many years, but she was raped there. She had a baby, the baby died, and then she developed this psychiatric illness. At some stage, she was taken to this institution.

When I found her, she had bipolar mood disorder and she had severe mental illness. Then I invited some of the psychiatrists for their assessment, and Rokea started to receive medication and she was responding so well. She told me about her story.

So I knew that she was a teacher and I created a crèche facility in this institution. I appointed her as a crèche facility teacher. She was very happy. Then she said that she would like to see her daughter. So we took a permission from the authorities and took her to that village. But her husband didn’t accept her. They didn’t allow her to see her daughters. Her own family didn’t take her, so she had to come back. She relapsed. Her treatment started again. So my question at that time was, who is responsible for Rokea’s mental health? And why it is happening? Or if someone experienced this sort of mental illness, then how to support them? Because at that time there was only Pabna Mental Hospital and in Bangla, that means “mad peoples jail”. So people were taken there and tied and caged and treatment was only medication and it was very difficult for me to find any solutions locally because there was no other model.

So I actually created some livelihood options for these girls, these women, who were staying there. And I have seen that when we actually engage them in addition to medication, when we engage them in activities, a purposeful activity, when they create something for them or for others, when they’re actually supporting each other, then that actually helped them a lot to going back to normal life.

So, I’m talking about 1992 to 1999. I was responsible for seven centers in Bangladesh. I tried to create a model there that can help them in their rehabilitation. And then my life changed again. In 1997, I met a survivor of an acid attack. I was horrified. I was shocked. I couldn’t understand what happened.

MV: Can you tell us a little bit about, very briefly, the history of acid violence in Bangladesh?

MR: Acid is a very corrosive chemical and it can not only destroy the skin. It can go very deep inside the bones and it can create permanent disfigurement. This problem started in late eighties in Bangladesh. The young girls were thrown acid by the young men when they refused a romantic relationship or a marriage proposal. That acid was used by the perpetrator to take revenge. The men did that with an intention that, “if this girl is not mine, she will not be anyone else’s”. And there was no awareness about this acid attack. Even I didn’t know about acid attack.

MV: Was it very taboo as if someone, if someone had been attacked, they did not want anyone to know? And it was something that the family wanted to keep very hidden and there was no justice?

MR: And no, yeah, there was more like the women were blamed for this act. Like what did they do? Why did they raise your voice? Why did they say no? So they were ostracized and there was no treatment facility in the country. Therefore, they had severe disfigurement, which was also difficult for them. So it needed a holistic approach. It’s not just treating them medically. When they go back to the village, they are still ostracized by the community. They are not taken back to school. They thought that other people are horrified by seeing them. And then they become completely a burden of the family. And the treatment, the plastic surgery, reconstructive surgery, that takes long time and it’s very expensive. Over the period of many years, the only treatment facility was available in Dhaka, and there were only eight bed capacity for all types of burns for 160 million people.

So you can imagine how difficult it was for them and then, because it’s a criminal offense, they were under threat. So not only they are receiving the expensive treatment – economically, they are suffering because they may have to sell whatever they have and they’re going through the pain and all this surgery – but also they have to face threats, the whole family, because maybe they have filed a case against the perpetrator.

So there was no organization in Bangladesh to support them and government didn’t have any services for them. There was no law to combat acid violence or providing the adequate services to the survivor so Dr. John Morrison from the UK and I started trying to find out what we can do. We established Acid Survivors Foundation in 1999. First we concentrated on the medical aspect because it was the immediate need. We had to save life. We had to minimize disability. We had to ensure that they can go back home in a safer way. They needed physiotherapy and other types of treatment protocols to actually get better. But when we started working on the medical intervention, we found that actually this is not just about the physical treatment because every year, we were seeing that some of the survivors ended their lives and at least 12 or 15 survivors were developing severe mental illness. We had to admit them in a specialized hospital for treatment. So, we needed an intervention for their psychological treatment, counseling, and psychosocial treatment. And again, there was no psychological or psychosocial intervention in the country. I told you about 1992, I didn’t find that. Now in 1999, I was still searching for that. In 2005, for the first time, we appointed a clinical psychologist.

MV: In the Acid Survivors Foundation?

MR: In Acid Survivors Foundation. We also, by that time, we started in a hospital, a 20-bed hospital, a 40-bed rehabilitation center, and we were bringing experts from the world.

MV: It’s a huge, huge improvement.

MR: It’s a huge, yeah.

MV: Small, small scale compared to 160 million people, but compared to what was initially there.

MR: Yeah, we actually wanted to create a model. This activism created a National Burn Institute and they incorporated burn and plastic surgery in the medical education. Earlier there was no plastic surgery courses.

MV: It’s amazing.

MR: So this movement also resulted in 2000 of having two laws: one for speedy trial of the perpetrator, and one for banning the availability of the acid in the open market. We also created committees to monitor the implementation of the law and they created the fund for supporting the survivors. But then all of that was happening in the Dhaka city. But when the survivors were going back home, there was no support services in the community. So we partnered with different organizations and connected with them with those organizations to develop their capacity. We developed psychosocial support providers at the community level. And most importantly, we developed many survivors as peer support providers. and psychosocial support providers. So my mission was to bring down these acid attacks. You know, it was rising when we started. It was rising at the rate of 40 percent each year. And it rose to about 500 attacks in 2002. And then we had the law in 2002 and then it was coming down. So by 2012, it came down to 50 attacks per year.

MV: So you brought it down 90%?

MR: Yeah. And then by that time we have created this holistic model, that biopsychosocial model. So the legal support, the rehabilitation support, the medical support, all are working together. We started the prevention campaign. The celebrities joined us. The students came forward. There was a huge movement in the country. Media was hugely engaged in this campaign.

MV: So how did this experience start to get you to think about mental health and wellbeing on a wider scale for everybody, not just for survivors of violence?

MR: So that inspired me to think about what we need to do about mental health. Because we all have mental health but our mental health can be affected any time in any way. And we need support for that. So that time mental health is governed by the 1912 Lunacy Act, which considered these people are lunatic. They’re harmful, they need to be institutionalized or cased.

MV: Kept away and can’t be a part of society.

MR: Yeah. The people with mental illness, they are ostracized, facing huge stigma around, there’s no treatment facility, no holistic approach, no psychosocial support system, and no prevention work. There’s no counselors in schools for the children. So then I thought, now I need to do something for mental health. By that time I became an Ashoka fellow. As you said, I’m a changemaker. Yes.

MV: You were a changemaker before you became an Ashoka fellow.

MR: That’s true. That’s true.

MV: They just recognized you for all your hard work.

MR: They recognized me as a senior Ashoka fellow and this enabled me to visualize what can happen, what can be done in mental health. In 2014, I started this Innovation for Wellbeing Foundation. Because for the wellbeing, we, know that there are people who are suffering from mental illness, but we can prevent that. Maybe we can reduce that number. We can limit that number if we are working on wellbeing. So if people’s wellbeing are good – wellbeing means not only physical wellbeing; it means psychological wellbeing, social wellbeing, spiritual wellbeing, financial wellbeing, emotional wellbeing – then we can say there are resources to tackle their mental health situation in a better way.

So we wanted to focus on wellbeing aspect and mental health aspect. And innovation because there was nothing in the country. So what is the solution for Bangladesh? We cannot just bring something from the Western country.

MV: And you think, and Well being is a Western concept or?

MR: Well, the solutions, most of the services, have been developed in the Western countries, especially for mental health treatment. So wellbeing, we have a lot of practices, but they were not considered as wellbeing practices.

MV: So thinking about mental health, that was growing, but then to really bring it together with the concept of financial, physical, spiritual, social, emotional, psychological health as well, as a holistic approach to wellbeing, was not quite the norm or understood or practiced?

MR: Yeah, not understood. Mostly mental health was considered as mental illness. Mental illness is not mental health. Mental health is my potential. Mental health is my ability to work for myself or for others. Ability to manage, cope with my stress. And live a normal life. But when we consider that mental illness, then all this stigma comes.

MV: And it’s the flip side of a positive thing. It’s an illness. So there’s a negative connotation there as well.

MR: Yeah. And language plays a very important role here. So how we address this people who are suffering from mental illness? Lazy or making up or not real? It is forever? They’re worthless? So all this kind of language is actually –

MV: Judgment.

MR: Yes, very judgmental, not only very judgmental but there is no hope. There is no possibility. There is no way to come out from this situation. So that scenario has to change. And that is also because of the law. When the law is saying it’s lunatic, then people think the same way. So first thing was for us, how to change this law.

So Innovation for Wellbeing Foundation created a network called Bangladesh Mental Health Network. And this network started working with different sectors, including people who has experienced mental illness and their family members to change this law. What should be the law? And we drafted an alternative law and finally, in 2018, Bangladesh government passed the Mental Health Act, 2018, which was much more accepting that this is a condition and there are also different types of solutions, but still it was much more medical-model-focused. And in medical model, also we have to consider that whether this is a holistic approach, because it’s not just about giving the medicine, but about whether you’re giving the counseling, whether you are giving follow up services, whether from recovery to rehabilitation to reintegration, whether we are providing these services or not.

And there’s no community-based mental health care support service system in Bangladesh. So our next challenge was how to create that model, how to create a model that will be much more holistic, much more applicable for different types of audiences. One size cannot fit all. Everyone is unique so that was a huge, it’s a huge area. So we tried to focus on three main areas. One is obviously would like to integrate mental health support within the primary health care support service system. Then, another priority we have is to introduce counseling, at least mental health first aid programs, in schools. By that time in 2015, we got the license for introducing mental health first aid program in Bangladesh.So that actually created a huge change because that increased the mental health literacy. And also helped to reduce the stigma around mental illness.

So now in 2024, I see quite a quite a change in this field. Actually, we were only one organization who started working on mental health. And now we have many organizations who are focusing on mental health. We just finished this Regional Wellbeing Summit, which is a kickoff actually to shake us and start a conversation. What is the wellbeing solution for us? What does our country actually need to focus on? How can we support each other? I’m very happy that we had this summit.

This is very special because now we have many actors in mental health field who are active and engaged, to collaborate, to work together, to make a network, a platform for this wellbeing movement in Bangladesh. So we created that network through this wellbeing summit.

MV: So, The Wellbeing Summit Dhaka: it was the first Regional Wellbeing Summit in Asia. Congratulations for that achievement. The theme was Prajano…

MR: Projonmo theke Projonme: Generation to Generation.

MV: And you were at Bangla Academy, a very important place for Bangladesh, a place to celebrate the Bangla language. You had the people there from all areas of work, the youth to the elders. Tell us a little bit about how the event connected with the land, language, and life.

MR: You know this summit talked about why individual wellbeing is important and why it is important for collective wellbeing as well. We talked about how social resources around us are actually supporting our wellbeing. We talked about social and emotional learning. In Bangladesh, in a hierarchical society, is a very, male dominant society. It’s very difficult to deal with your emotion, to express your emotion in a healthy way so women are suffering silence. And men also suffer because in a way they are socialized so that they cannot also express their vulnerability. So what we try to give them a safe space here and have that conversation, what are the barriers and what are the opportunities, what is available actually, and what will be in our future wellbeing agenda for the country. We don’t have even a wellbeing strategy in Bangladesh. We have national mental health strategy. We have a national mental health policy. That’s good, but that is again talking about more what to do after we are suffering. So I think this wellbeing summit is very unique in a way that created an opportunity for us, especially for changemakers, to be together, share their experiences and learn from each other. And also the therapeutic interventions, these art interventions, we have seen that how these artists, the painters, the singers, all the other artists, how they actually engage these people.

MV: It reminds me of, you said the first thing you did with your work as a social worker is you brought the postcards and the coloring and the paper, and that was one of the first ways you were able to engage with people.

MR: Yeah, and I believe that because I have seen that with the survivors of acid attack, I have seen that with the homeless people, the sex workers, and, many other marginalized communities that we work with. Visualization is very important.

Then sustainability: this is the challenge for Bangladesh. We are from Delta and we have very fertile land, but also it’s very prone to disaster. And therefore, it’s very important that we connect this land, the fertility, with wellbeing. Wellbeing always give that fruitation that brings something meaningful into our life. And then also with disaster: we have resilience. We build our resilience. Life has adversity. It will continue like this, but the resilience that we are creating and the way we are supporting the whole nation is supporting each other. That’s the model: how to help themselves and in their daily lives. How to create a safe space. How to live without fear. Fear is a big issue limiting us. So it’s very important that we can, we can actually win this fear. So all theses tips and tricks and fun and all these things, I think it’s all together. I feel like it’s created a new energy.,

MR: And with new energy, what is coming next? Or what needs to come next? Or what do you see already emerging? What do you see for the future of this? Because when we talk about wellbeing for social change, it’s well being in two ways: a culture of inner wellbeing for change makers, but also in changemaking. So normalizing the concept within social change, which is already there, but maybe just knowing that a bit more concretely. And also within the social change sector so changemakers and organizations have those structures in place to encourage that. What do you think is coming next in Bangladesh?

MR: Yeah, it’s important to create a model that can be replicated for the whole country. It has to be cost effective. It can be done with whatever existing resources available. And it is received by the people. What is their aspiration about the next step? It’s important to continue this conversation. Maybe we will start small as like I said, like Acid Survivors Foundation started with a small thing, but that created, as I told you, the National Institute for Burn and Plastic Surgery. And now we have changed the law for mental health from the Lunacy Act. Now we have the National Mental Health Policy, the strategy paper. And obviously one size doesn’t fit everyone, but it has to be from within our local cultural context, the social structure, and the human resources that we have. And I believe that everyone has that capacity, the resources, the ability. We just need to create that opportunity for them. And if we are able to educate and train people, they will be a great resource for the community. And that might be the solution for Bangladesh.

MV: Monira, you have told us about your work, you have told us about your career, about the amazing things you’ve done, the changes that have been taking place in Bangladesh, you’ve told us about your impressions from the Wellbeing Summit Dhaka… and my last question: You’ve mentioned a few things as you were explaining to us about your work and starting from your times in university to your first role as a social worker, then through the Acid Survivors Foundation, now with Innovation for Wellbeing Foundation. Under all of that, at the heart of your work as a social changemaker, what is your motivation, your inspiration, your dream? Your message to the world? What is there?

MR: We all are connected wherever we are and whoever we are and whatever we are doing. It’s very important that everyone is content and happy and living the fullest of their potentials and also that we work as a community, an aware community. And by collaboration, by working together, by supporting each other, we can actually advance much more. We can progress much more. We can do much more for ourselves as an individual, for our family, for our community, for the planet. So this is my aspiration that we really need to looking at Ecological Belonging and we need to connect to the life and the planet together.

MV: Well, thank you so much, Monira , for speaking with me today live in Bangladesh. It’s been a true pleasure. Donyabhat. I hope I said that correctly.

MR: Yes. Yes. Yes. Very well. Donyabhat.

MV: And we’ll see you soon. Thank you.

MR: Thank you. Thank you, Madelaine.

Thank you for listening to this episode of, At The Heart Of It. For more news, research, and stories about wellbeing and social change, visit wellbeing-project.org. The Wellbeing Project is the world’s leading organization advocating for the wellbeing of changemakers and for wellbeing in changemaking. We believe wellbeing inspires welldoing. Thanks for listening and see you next time.